Claudia Kelly of Gate 6 ½ sends along this excerpt from the book Down by the Bay—San Francisco’s History Between the Tides:

What do silver, salami, steel, wine, and lawn furniture have in common? Maybe a picnic with proper silver cutlery on the lawn comes to mind?

What needs shallow water and wind and is one of SF oldest industries? No more questions, just the answer: salt. And local good news is that the salt refining ponds of yesterday have been repurposed as bird refuges with brine shrimp as ideal food for migrating birds. Nice reuse of a very toxic corrosive chemical used in making DDT, chorine, gas, bleach, explosives and lawn furniture. Also, PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) used by manufacturers to keep electrical transformers from overheating and exploding. Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastics show up in lawn furniture to plastic-wrapped meat trays at the grocery store.

From the sky these ponds are gorgeous bright colors reminiscent of Japanese art prints: lime green, orange and rusty red not brown like the adjacent muddy bay shallows roiled by wind and tides. Color comes from bacteria that thrive in the saline environment. For the migrating fowl, a nice free lunch or overnight stop in their transit from Canada to Mexico. These ponds constitute the first and most extensive Urban Wildlife Refuge. Since 1960’s the federal government has been buying up the salt ponds and converting them into bird habitat.

Up to 1848, people gathered enough salt for their own personal use but that changed with the discovery of the Comstock Silver mines where salt became a principal ingredient in the industrial development of California. In 1857, the “patio process”, learned from Mexican miners, required volumes of sodium chloride to refine pure silver from raw ore. No salt by-product was more valuable than chlorine; chlorine made from San Francisco Bay salt bleached toilet paper white in Pacific Northwest paper mills, purified Los Angeles’s drinking water and treated San Diego’s sewage.

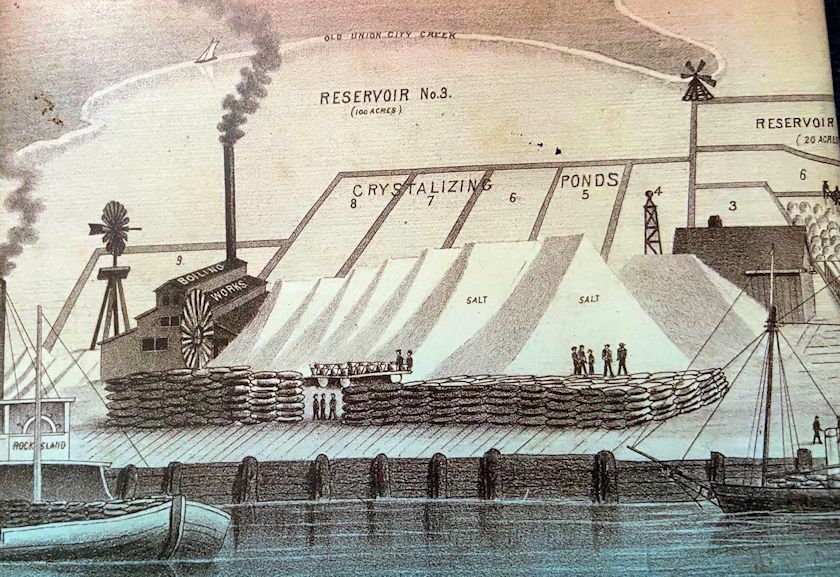

Sodium chloride evaporation thrives on wind driven shallow ponds and can also be mined from underground deposits left by ancient seas but the world’s largest mineral reservoir is the oceans. This “white gold” undergirds the 20th century revolution in water treatment, that together with vaccinations, lengthened average American lifespan by 20 years. It was used in corrosion-proofing steel, gas and oil refineries. SF was once the hub of a regional chemical industry. As salt transformed from personal consumption into a key ingredient in the industrial development in California, the scale and production also changed. Gathering could be eased by placing wooden stakes or bundles of reeds to offer a surface for the salt to crystalize on. Making salt on an industrial-scale product first required owning means of production. Like all other tidelands, the salt ponds have a convoluted legal history. Many of these waterfrontage lands fell into private hands through corruption and Mexican-era land grants which legally ended at high tide. It fell to the surveyors to mark the lines between tidelands and swamp and overflowed lands. It was no wonder that tideland titles, which gave access to the bay, became so valuable that they were worth stealing.