The recent high winds, coupled with the PGE shutoff—though inconvenient and even challenging for some—were easily survivable. What if events had been of a higher magnitude: people trapped or injured, collapsed structures, and outbreaks of fire? The stuff we train for as CERTS. How well would we have responded?

A few weeks ago, South 40’s Stewart Brand tweeted, My adventures working on rescuing people in the San Francisco Marina after the Loma Prieta earthquake 30 years ago. Volunteers saved the day. I chronicled how that worked. [along with the link] LEARNING FROM THE EARTHQUAKE.

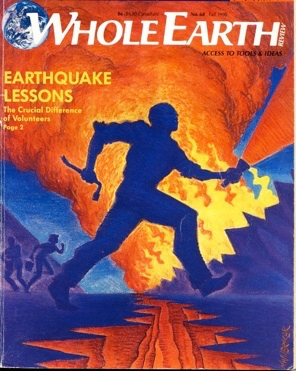

The Loma Prieta Earthquake of Oct 17 1989 struck at 5:04 p.m. just as Stewart was passing by the Marina. He was both the right person in the right place to join the rescue efforts, and very much the right person (as a journalist) to reflect upon, and examine, how volunteers and rescue workers responded in those first hours of the unfolding disaster. A condensed version first appeared in the S.F. Chronicle, with the full version published in the Whole Earth Review, fall of 1990. “This article,” Stewart writes, “is an attempt to reconstruct the confused events of that first two hours at Divisadero and Beach, and to distill some advice that might be useful to anyone wishing to survive a disaster and to help others to do the same.”

Following the earthquake, where the main press put a positive spin on rescue efforts, featuring heroes and in general glossing over the cumulative errors, Stewart wrote the (untold) story of the volunteers. Volunteers who stepped in well before rescue teams were on the scene. Volunteers who hauled fire hoses, managed traffic, formed ad hoc teams and in myriad ways rose to the occasion.

But he also wrote a cautionary tale in his examination of the psychological states of a disaster, and of bystanders—who could have volunteered, or been asked to pitch in had someone simply asked. And he looked at how valuable tools were left behind in the rush to get to the scene, as well as the merit of jacks and blocks over purpose-built tools (Jaws of Life) when working in tight spaces.

The stakes were high: people died, fires broke out (and fire hydrants failed). “Volunteers were the message carriers all evening” (remember this was pre-cell phone, though even today could we count on cell phone coverage during a power outage?), severely hampering coordination (which was, in any event, sorely lacking).

Organized into 2 sections: Part One: THE MARINA FIRE and Part Two: EARTHQUAKE BEHAVIOR, Stewart artfully presents a gripping (and—be warned—lengthy) narrative. The detailed accounts—from the numerous volunteers and fire and law enforcement personnel Stewart interviewed—place the reader at the scene, warts and all. Not everything went well, though some things went extraordinarily well—the whole lot is mined for lessons learned.

Along with lessons (highlighted and repeated, the better to make them stick), Stewart provides lists of tools, and insights gleaned and extracted for easy perusal. Helpful information for those wanting to get a leg up on a disaster well before it strikes. I would almost go so far as to say this should be required reading for CERTS-in-training, if not for any floating home resident. Should disaster strike, we will likely be in the best position, and with the best knowledge and skill sets, to rescue ourselves.

Looking back over the past few PGE shutoffs, what could we have done differently?

In case you were wondering, the FHA is currently looking back at how best to prepare for, and weather-in-place, the PGE shutoffs and similar events—culling through a long list of tips and tricks, and anecdotes, sent in by members of the community. Keep an eye on this space for the results.