I’m wandering along Issaquah looking for the Box Poem when I see three people laughing, mugging for photos beside sculpted faces mounted on the pier railing. They’re in front of Box Poem. It’s Jim Woessner’s boat and he created the sculptures that are attracting attention.

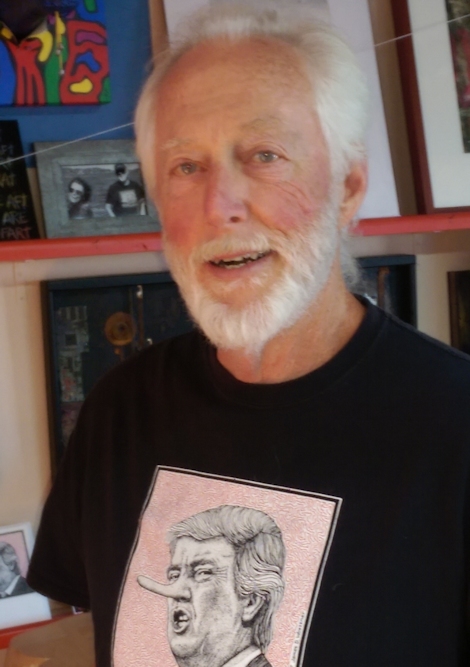

Opening the door, I step inside a fertile mind. Floor to ceiling, there’s vivid color, black and white, realistic and abstract paintings, collage and sculpture. Papier mache balloons hang from wooden ceiling beams—one looks like a birdhouse but has a miniature artist’s studio inside. In the middle of it all, Jim sits at a long, tall table, his laptop open beside him.

He’s an experimenter, always trying new ideas and methods. Lifting a framed dot drawing of a leaning boat at Pt. Reyes from the wall, he runs a finger over it. “This is about 500,000 dots,” he says. “I won’t do that again!”

Jim grew up in St. Louis but spent much of that time in the Ozarks where his family owned a fishing cabin on the Big Piney River. There he explored the woods and water as a child. Always curious and imaginative, he didn’t get much support for those traits. In fact, a high school history teacher told him to settle down and curb his imagination. So, he earned a bachelor’s in engineering from the University of Missouri. But instead of heading to California, as he dreamed, he was drafted. He spent his next 5 years as an officer in a nuclear submarine during the Vietnam War. That led to a master’s in nuclear engineering and 30 years in quality assurance. He worked for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and in the chemical demilitarization industry destroying chemical weapons. In 2012, he retired to pursue art full time.

After earning a master’s in fine art, Jim taught creativity workshops—first for children, then adults, and in corporations. Eventually he wrote a book based on his teaching, Creativity: Crossing the Threshold.

“I’m primarily a sculptor,” he says. But he lost his studio in Sausalito five years ago when the rent jumped. “Sculpture is noisy and dirty, so I really couldn’t do it here. That focused me on my writing.” In 2014 and 2015, Jim published three books of poetry. Two years ago, he named his house after the type of poetry he writes—box poems*.

The pull of sculpting remained though, leading him to balloons. “I really needed to get back to working with my hands.” He picks up a paper cutout of a baby’s face. Underneath it is a sketch he’s working out for his next balloon—an egg cracking, the human baby’s face peering out, wide-eyed. “Balloon media is easy to do here. I can clean up the mess in 5 minutes.”

Jim’s a long-timer in the floating homes community: 30 years. He was the driver behind Issaquah dock’s artist focus, founding Artists of Issaquah and the first Artists of Issaquah Show in 2003. He ran the Issaquah show for 10 years. He’s organized a men’s group for the last 6-7 years, all of whom are artists or involved in art in some way, and he participates in an informal writer’s group. “I’m a very social person and enjoy the camaraderie.” It’s what he likes about living in this community too, socializing with neighbors on the dock. “People enrich my life,” he says.

A sculptor, a painter, a poet. Given Jim’s creative range, what’s next? “I’m working on a book of character-driven short stories.” He’s quick to say he’s avoiding conventional approaches. He’s creating unconventional characters too, exploring their psyches. His style’s more James Thurberish. “I want to transport a person to someplace he or she hasn’t been,” he says. “To take a reader to a place they don’t expect, the writer often discovers it the same way. I want the stories to surprise me as much as they surprise the reader.”

As we talk, I note that some anecdotes from his poetry are coming up in his short stories. “A lot of common ideas and images show up over a body of work,” he says. A common character for him is the curious boy. “Every short story is autobiographical in some way—something that happened or that you noticed, or a sense of something—you don’t remember all the stuff that happened. I was kidnapped when I was 5,” he says, then goes on talking about the creative process.

“Wait!” I say, “you were kidnapped? What happened?”

“It wasn’t real traumatic. A bunch of thugs.”

They grabbed Jim and two young boys not much older than him from a patch of woods and locked them in a shed. “Within a few hours, we pulled up the floorboards and escaped.” Somehow, that experience feeds into his short story that opens with boys playing in a cave in a central Missouri town. They discover a dead body.

One of his box poems is about a neighbor commiserating with his mother who’s complained that Jimmy’s being strange, running around the yard flapping his arms and thinking he’s a bird. Jim’s poem ends with: “What if I ended up believing her? What if I had forgotten how to fly?”

* Links to Jim Woessner’s box poem publications can be found at the Boatload of Books