Even though Jay Lalezari’s floating home at 19 Yellow Ferry Harbor isn’t on the main walkway, it’s difficult to miss. It’s a three-story with a huge squid on the side. There are butterflies, a mermaid and progressive political signs too. Tourists often stop to take pictures, and Jay sometimes invites them in and shows them around.

When he does, Kaya, Jay’s canine companion since she was a puppy, eagerly greets them. They’ve lived in this community 8 years, the first year on Issaquah. To help tell the two of them apart, Jay posted their rotating pictures on his company website ; one photo is labeled Doc, the next is labeled Dog. Just to be clear. Jay is CEO of Quest Clinical Research in San Francisco. He’s a research doctor with a poet’s soul.

Jay grew up in Scarsdale, NY. In 1982 he earned a Masters in English Literature, then four years later an M.D. Why the disciplinary switch, I wondered? “I got absorbed in Paradise Lost and my dad gave me an ultimatum,” Jay tells me. “He’s a research immunologist from Iran, an Ayatollah dad. He made me go to medical school.”

Living in San Francisco was Jay’s fantasy. He arrived with his medical credentials in the early years of the AIDS epidemic. “I was drawn like a moth to a flame,” he says. He’s not gay, but this crisis and the opportunity to help fit right into his family history and dynamics. It simultaneously countered his father’s homophobia and indirectly repaid the altruism shown his mother. She “was a Holocaust survivor. Nuns hid her in a convent for years, at their own risk.”

In June 1989, Jay began AIDS research at UCSF. The next year, police brutality sealed his commitment to the cause. Speaking at an Act Up event, he was humiliated when instead of a positive response to what he believed was hopeful news about potential drug treatment, activists staged a die-in during his speech. They fell to the ground, outlining their bodies in chalk. Suddenly, 20 riot police charged in with batons, bloodying the crowd. “It was entirely out of proportion to their crime of chalking sidewalks,” he said in a KQED interview. He was outraged and “radicalized on the spot.”

Besides HIV, Quest worked on Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines. With the substantial progress in those areas, he’s branched out. They’ve just started breast cancer research and gene therapy and stem cell research. “Non-alcoholic fatty liver is epidemic. It’s the most common reason for transplants,” Jay tells me about one of their new directions. I’m surprised by this and ask him why. “Because of all the junk food. Sugar mostly, I suspect but I don’t know for sure.” Quest is working on developing a pill to treat it.

Ah, the drug companies. We talked a lot about the pharmaceutical industry and healthcare. “Working with pharmaceutical companies is dancing with the devil,” Jay acknowledges. “But it’s more ambiguous than that. They’re a heinous industry, but they’re the ones that cured AIDS.” People living with HIV now have a pretty normal life expectancy. People with AIDS also contributed to the cure, though. Thousands of AIDS patients participated in studies when they knew they wouldn’t live long enough to benefit from it themselves. “That’s the untold story of altruism,” he says.

Jay moved to the docks after a divorce. “I’m an East Coaster and had a beautiful house in the Mill Valley hills. Then suddenly my marriage was over. Getting an apartment on land, I’d curl up and die.” The idea of living on water had never occurred to him, but he needed to do something different. Now he says he’ll never leave. “There’s such a sense of community here and that’s falling apart in the world.”

Jay credits the Mankind Project’s New Warrior Training Adventure program with saving his life. “It’s all about helping a man see and touch his shadow, stepping fully into and breathing the clean air of integrity and accountability, and reframing life away from a game of not getting caught to an authentic life where we can call ourselves out with love for our failings when needed.” You might find him at Burning Man, too. “It’s the best party on the planet. I go there to fall in love with people and myself all over again.”

As we walk through Jay’s home, there’s an altar on a hallway wall, landscape paintings, a yellow Honduran mask hanging in a corner and beautiful wooden beams and stair railings. We step out onto the rear top floor balcony. “It’s the hot tub that sold me,” he jokes. One of the bedrooms downstairs is his son’s when he visits. Thirteen-year-old Max was just bar mitzvahed, he tells me, nodding toward his son’s picture. The other bedroom is “where friends stay when their lives fall apart. It’s been used quite a bit.”

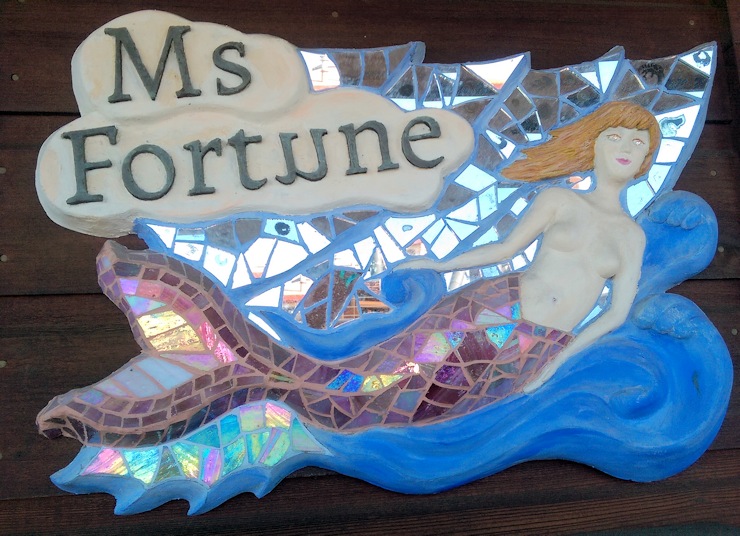

“Misfortune is what brought me to the houseboats,” Jay says with a grin as he points to the mermaid sculpture by the front door. She’s sweeping upward toward her name, one that signals a turnaround: Ms. Fortune.