The first large ethnic group to move to Marin in the 19th century were Portuguese from the Azores Islands. One sign of this heritage is the Portuguese Cultural Center at the Northwest end of Caledonia Street. The entrance is labeled “IDESST Center”, or “Imandade do Divino Espirito Santo e Santissima Trindade”, translation: “Brotherhood of the Divine Holy Spirit and Blessed Trinity”. On Pentecost Sunday each year several young girls are chosen to be Queens for a Day and lead a parade from the Center to a mass at the Star of the Sea Catholic Church, and then, escorted by fire trucks, parade along Bridgeway. The Portuguese were boat builders, fishermen, and dairy farmers. Many Marin hill sides became home for these dairy farmers, while fishermen and boatbuilders worked along the shores of Sausalito.

Catching herring

The only fish to actually come into Richardson Bay from the Pacific Ocean in large numbers are herring schools that lay their eggs along the rocky coast of Sausalito in November, December, and January. The dramatic photograph above (Fig. 1) was taken in 1955 on the north edge of Old Town. These men were able to net fish from the shore because that’s where female herring go to lay their eggs.

I moved to Sausalito in the year 2000. From Thanksgiving past Christmas, about 20 herring boats (Fig. 2) spread gill nets in Richardson Bay. I learned that the net was fed out over a roller in the bow as the boat backed away slowly, with the floating edge of the net marked by lights to keep other boats away. The most productive time to net was night to early morning. After a few hours the net was slowly pulled back over the bow roller and while a larger roller vibrated to make the trapped fish fall from the gill net into the hull. The characteristic noise of the shakers and the circles of net lights that occupied much of the shore was a part of winter nights in Sausalito. The size of the catch could be estimated by how much lower the boats were in the water after the catch, often several feet; they were each netting tons of fish.

Sport fishermen can catch herring with a smaller cast or throwing net. These nets are typically 10 feet in diameter with small weights around the circumference. You throw it out over a fish school, while twisting your body to cause the net to rotate slowly. This motion causes the edge of the net to expand into a circle which sinks, trapping the fish inside. Pulling the net back closes the open end trapping the fish.

Eating herring

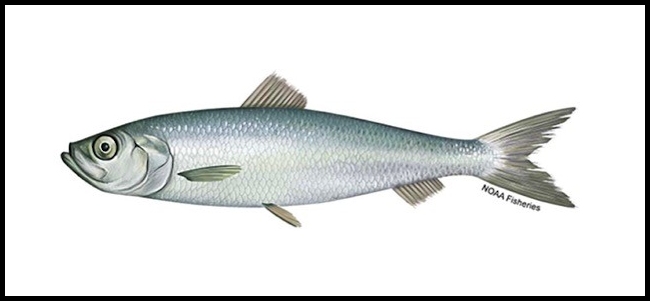

Herring as food is complicated. You can eat the fish itself. Adult herring (Fig.3) are about 5 inches long, like a big sardine, and have a strong, oily taste. They can be salted, smoked (then known as kipper), or pickled. I have enjoyed herring from our Bay, but I like sardines. Evidently, I am in the minority, as herring don’t sell well here, and mostly end up as food for cats, farmed salmon or even dumped as landfill. However, some destination restaurants, e.g. Berkeley’s Chez Panisse, occasionally have herring on their menus.

Herring eggs, the roe or caviar, taken from the female before she can deposit them, represent the main value of the fishery. Herring roe is prized in Japan as kazunoko, and are part of celebration of the new year. Most of the value from our herring is in the roe shipped to Japan. Herring can deposit their eggs on just about any solid surface. Eggs deposited on kelp, komochi kombu, are also a delicacy in Japan. In January of this year (2024), when small herring schools were visiting Richardson Bay, I observed a catamaran barge at Schoonmaker Marina being baited with long strands of kelp that had been collected from rocks north of Santa Barbara. The barge was to be anchored for several days in the Bay when hopefully herring would deposit eggs on the kelp which would then be processed and sent to Japan.

Where do babies come from?

A question once asked of their parents by many children. Now children probably just Google it. But we, dear readers, know the answer already: babies come from eggs. While mammals fertilize their eggs, then incubate and nourish the growing embryo internally, fish, birds, and reptiles deposit large eggs that consist mostly of yolk. The yolk is the food that enables development and growth of the single fertilized cell into the thousands to billions of cells than make up a juvenile animal that is able to hunt and eat its own food. Since the herring egg is almost transparent, we can observe the fish grow and differentiate inside its outer coat.

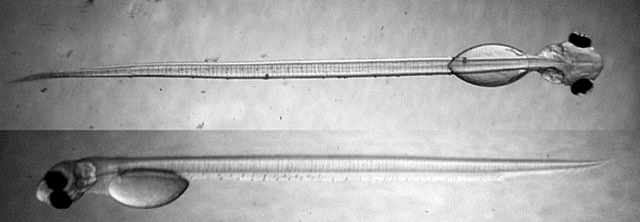

The herring stays in the egg for about 20 days while growing in size and developing all the parts it will need to survive. A few days before hatching two large dark objects appear in each egg (Fig. 4). These are its eyes! All eyes must contain a pigment that converts light photons into electrical pulses that are transmitted by nerves to the brain to be processed, resulting in muscle contractions that enable the animal to survive. Since these pigments absorb light, they must be dark. Aside from the head, most of the remaining body is a long thin tail that is wrapped several times around what remains of the yolk sac. This tail enables the fish to swim.

These photos (Fig. 5) are side and top views of the fish just after leaving the egg case. I said the tail was thin, and you see I wasn’t exaggerating. The pouch just posterior to the head is not its stomach, but rather what is left of the yolk sac. This will nourish the fish until development is completed, e.g. functional jaws and digestive system. It must also learn to swim, catch prey, and hide from all the bigger fish.

Where do babies go?

The ones that will survive and become adult fish go someplace safe; dense eelgrass beds are good choices. Even there the chance of a baby herring growing up is very small. Each female herring lays hundreds to thousands of eggs, but only one or two will survive to lay eggs for the next generation.

Babies must grow rapidly so they are not eaten. Their own prey need to not be so small as to be a waste of energy to chase but not too large to swallow. Copepods (Fig.6) are just the right size and are a major part of the young herring’s diet. Copepods, typically 0.3 to 3 mm long, are so numerous that even though individually small, they represent a significant fraction of the total biomass in the ocean. Copepods are arthropods, animals with hard outer shells and jointed arms and legs. Terrestrial arthropods are called insects, while marine arthropods are known as crustacea. Crabs, shrimp, barnacles, and copepods are all crustacea.

Copepods reproduce sexually; the female typically holds eggs as a cluster on her abdomen which are then fertilized externally by males. The eggs hatch to produce (very) little copepods which eat, grow, and shed their shells periodically as they grow into adults. Adult copepods are just large enough to be seen without magnification. They swim by characteristic bursts of rapid contractions of the antenna and legs. Once you see a copepod swim you will always recognize them. A major prey of copepods are diatoms. We are working our way up the food chain.

Where did the herring go?

The number of herring and the boats fishing them in our Bay declined steadily from about 2005 onwards, and although small schools still come here, we no longer have a commercial fishery. However, herring still school in large number along the Northern Californian coast and up to Southern Alaska; commercial herring fishing is productive there. Most probably the warming ocean water, e.g. global warming, has caused the herring to move north to stay in the temperatures they like. Many animal and plant species have migrated north, or if living in hills and mountains, move higher. Humans have air conditioning, so they don’t have to move. Refrigeration requires a lot of energy, and if you get that energy by burning fossil fuels you increase the CO2 concentration of our atmosphere which warms the planet further. But that’s another story.

Fish in the service of science

Biological and medical research is greatly facilitated by studies of a relatively few specific organisms by international groups of laboratories. These species are known as model organisms. Examples are the bacterial viruses T4 and Lambda, the bacterium E. coli, the yeast Saccharomyces, the fruit fly Drosophila, the and the nematode C. Elegans. There are many types of experiments one can do: ecological, genetic, anatomical, physiological, biochemical. If a group of experiments are done using the same organism, the results complement each other and produce a coherent picture. If a large number of labs are using one organism, it becomes worthwhile to spend time and effort to isolate mutants and develop techniques that can be shared by all. Observations using many different organisms are of course also important, but special recognition is due individuals who, through intellect and often also by personality, have established the study of model organisms.

In 1959 I was a beginning graduate student at UC Berkeley starting research in Gunther Stent’s laboratory on T4. At that time this virus was studied in many laboratories partially due to earlier experiments by Max Delbruck, who was also influential in organizing and moderating conferences on this virus. Delbruck later received a Nobel Prize, mostly for this work.

Gunther had organized a trip to the University of Oregon at Eugene so all of his students could attend a conference on T4. On our way home we stopped and had dinner at the home of George Streisinger, a professor there and close friend of Gunther’s. The gossip in the ride to his house was about Georges’ crazy decision to work on Zebrafish, which were then just a tropical aquarium pet. Today, on Wikipedia you can read: “Over 9,000 researchers in 1,551 labs throughout 31 countries study zebrafish, and many of them received their initial training at the University of Oregon.” The university also serves as a center for the distribution of zebrafish mutants. One of the first mutants was Casper, named after the cartoon ghost, a fish deficient in pigment and thus transparent. This allows you to follow the development of internal organs. There are now many mutants in which the DNA sequence for a small fluorescent peptide has been fused to the end of a gene. Cells in the developing fish thus glow with a characteristic color if they are expressing this gene. Maybe George wasn’t so crazy after all.

What do zebrafish have to do with herring? While herring are larger, their anatomy and embryology are very similar to zebrafish. You will find many books, research articles, and articles on zebrafish, so you can satisfy your curiosity about the biology of fish.